English George. Altarpiece of the Joys of Santa María (detail), around 1455. Museo Nacional del Prado. Deposit of Almudena de Arteaga y del Alcázar, 20th Duchess of the Infantado, and Iván de Arteaga y del Alcázar, 15th Marquis of Ariza

The Prado Museum and the National Library review his work as a promoter of culture

Among the 15th century personalities who stood out in Castile for their attention to culture, in their diverse registers (from the cultivation of poetry and the history of literature to bibliophile and the promotion of the arts), it is essential to mention Íñigo López de Mendoza, the Marquis of Santillana.

Born in the Palencia town of Carrión de los Condes in 1398 and died in Guadalajara sixty years later, it is likely that he never left the Iberian Peninsula, but from his palace in the latter city he commissioned works that testified to his cosmopolitanism and his good knowledge of the new developments both in Flanders and in Italy: he entrusted paintings to Jorge Inglés, perhaps a German-trained painter, and resorted to agents and exchange networks when it came to getting hold of luxury books that, in addition to their content, valued for its material and artistic wealth and as an expression of prestige. He would compete, in this collecting effort, with other bibliophiles of his time, such as Alfonso the Magnanimous, Íñigo de Dávalos or Nuño de Guzmán.

In order to review his work as a cultural promoter and precisely as a bibliophile, the Prado Museum and the National Library of Spain have jointly inaugurated today the exhibition “El marqués de Santillana. Images and letters”, Javier Docampo and Fernando Villaseñor, both specialists in medieval books, began to work on the preparation years ago. After the recent death of both, whom the exhibition also wishes to pay tribute to, Joan Molina, Head of the Department of Gothic Painting at the Pinacoteca, and Isabel Ruiz de Elvira, Director of the Department of Manuscripts, Incunabula and Rare Items at the BNE, have followed in their footsteps.

The center of the presentation of this exhibition in the Prado is occupied by the aforementioned Jorge Inglés, in charge of carrying out, since 1455, three pictorial groups for the church of the hospital of San Salvador de Buitrago de Lozoya (Madrid), a charitable institution that the Marquis himself founded for the salvation of his soul. It is the famous Altarpiece of the Joys of Santa María , which was to be placed on the main altar and was deposited in the Museum a decade ago, and two triptychs, one dedicated to three holy knights and the other to three Franciscan saints, which are placed on the side altars. The exceptional Saint George and the dragon would form part of the firstthat has arrived at the exhibition and that stands out for the elegance of its white steel armor and the extravagance of the emerald green being that steps on it.

The choice of Inglés, active in the two decades that passed between 1455 and 1475, is worthy of attention: little is known about this author, and his very origin is confused, but his work reveals an evident attention to the sculptural value of the figures, the contours of the faces and the expressiveness of the lighting, traits that bring him closer to Germanic painters who, a few years earlier, had translated the Flemish models of the masters Van der Weyden or Campin .

Aside from his works for Buitrago, only the altarpiece of San Jerónimo from the Valladolid town of La Mejorada and that of the Virgin of Villasandino (Burgos) have been preserved from English, of which three panels dated around 1470-1480 are now on display. It was dismantled in later centuries and most of its compartments were reinstalled in an eighteenth-century altarpiece that is still part of that temple, but these tables that are now shown to us were torn off and reached the market. They underline, in any case, the role of the Virgin, Saint Joachim and Saint Anne in Christ’s plan of salvation and this altarpiece from Burgos presided over it, like that of Los Gozos, a carving of the Virgin with the Child, this time seated and flanked by two angels.

The exhibition, in room 57 of the Villanueva building, is completed by an examination of the marquis’s bibliophile and literary passion that, as we said, culminates in the National Library. He paid for the production of songbooks that collected some of his poems and that he gave to other aristocrats, thus transmitting his erudition but also forging alliances; we will see one surely conceived for that of his nephew of him Gómez Manrique in which the Joys of the Virgin are included, transcribed in the altarpiece of the same name, and the heraldic colors of the Mendoza are used in the illuminated initials.

Master of the Paulo Deacon (illuminator). Phaedo , Plato, about 1450-1455. National Library of Spain

From the library of Íñigo López de Mendoza, perhaps the most significant library of the 15th century in private hands in Castile, nearly a hundred volumes have come down to us, most of them preserved in the BNE and digitized. He possessed illuminated manuscripts in various specialized centers, from Toledo to Florence, including codices decorated by anonymous miniaturists who embodied a new Flemish-rooted naturalism, including the Master of Paulo Deácono, who filled his borders with animals and figures and distinguished himself by the folds broken from their angels, along the lines of those of English. He also dominated that northern aesthetic, the Master of Brianda de Luna: his border and his figure of Juan II in the capital seem to refer to the images of Burgundian miniaturists.

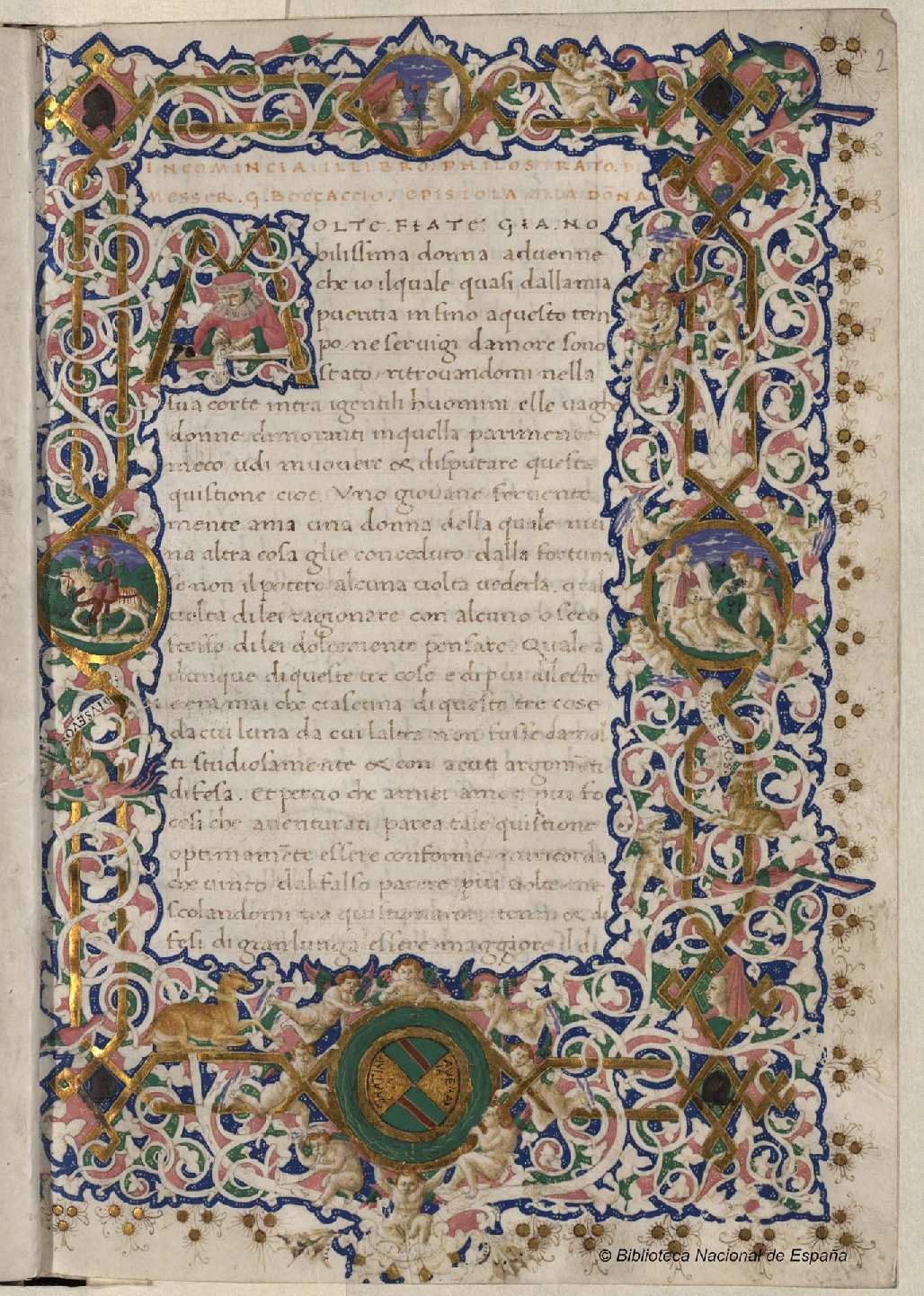

As we said, on occasions educated aristocrats established abroad provided him with jewels: Íñigo de Dávalos, we anticipated that a bibliophile like him, sent him from Naples an Italian translation of the Latin classic Historia de Alejandro Magno , with an initial decorated in bianchi girari ( intertwined white leaves and branches on a colored background) and two angels in grisaille that the Master of Brianda de Luna would add, already in Castile; We deduce, therefore, that the knowledge of Flemish painting in the Marquis’ environment was prior to the fundamental commission to English for the Buitrago altarpiece.

Borders like this, bianchi girari and populated with animals, angels, putti and some emblems of the nobleman, also frame the initial text of four Italian manuscripts: their decoration is due to Francesco di Antonio del Chierico, the Master of the Farsalia Trivulziana and the Miniaturist of the Marquis of Santillana, who worked for the bookseller and merchant Vespasiano da Bisticci, who in turn supplied manuscripts to such distinguished clients as the Medici . The Marquis agreed to it with the mediation of Nuño de Guzmán.

Likewise, López de Mendoza acquired old books with careful binding or decoration, such as the Libro de Alexandre , one of the first literary works in Spanish: his copy had embossed leather covers on a Mudejar-style board. His was also the manuscript of La Fiorita, by Giudice da Bologna, a moralizing encyclopedia copied in Italy at the end of the 14th century, to which, a few decades later, pieces such as a subtle drawing of a lady reminiscent of Pisanello were added.

Of the latter we will see in the Prado medals with portraits of Alfonso the Magnanimous and Iñigo de Dávalos whose reverses contain allegories. For them, and for other lovers of the humanist book, Francesco di Antonio del Chierico or the Master of the Farsalia Trivulziana also performed; his work shows, as Molina has underlined today, how sensual and sophisticated the pages can be.

THE JOY OF THE ALTARPIECE BY JORGE INGLÉS

Probably made between 1455 and 1475, its typology differs from that of most Gothic altarpieces, structured around a central image surrounded by narrative scenes. It consists of a horizontal register, in which the portraits of the praying patrons appear flanking the Virgin with the Child, and a large upper panel with twelve angels carrying phylacteries in which the Joys that the Marquis himself dedicated to the Virgin are written. The ensemble is completed, on the terrace, by three-quarter figures of the Fathers of the Western Church: Saints Gregory, Jerome, Augustine and Ambrose.

In what is strictly pictorial, the models inaugurated in the Netherlands around 1420-1430 are very present, in the sculptural and lighting values and in the accentuated reliefs, but the vigor of the drawing and the lines of the faces make English, either whatever his place of birth, in an interpreter, more than in a representative, of those formulas, surely trained in the Germanic area.

English George. Altarpiece of the Joys of Santa María , around 1455. Museo Nacional del Prado. Deposit of Almudena de Arteaga y del Alcázar, 20th Duchess of the Infantado, and Iván de Arteaga y del Alcázar, 15th Marquis of Ariza

“The Marquis of Santillana. Images and letters”

PRADO NATIONAL MUSEUM

Paseo del Prado, s/n

Madrid